ENCOMPASS II

Patricia Ready Gallery

Steel and industrial paint, 240 cm diameter

2015

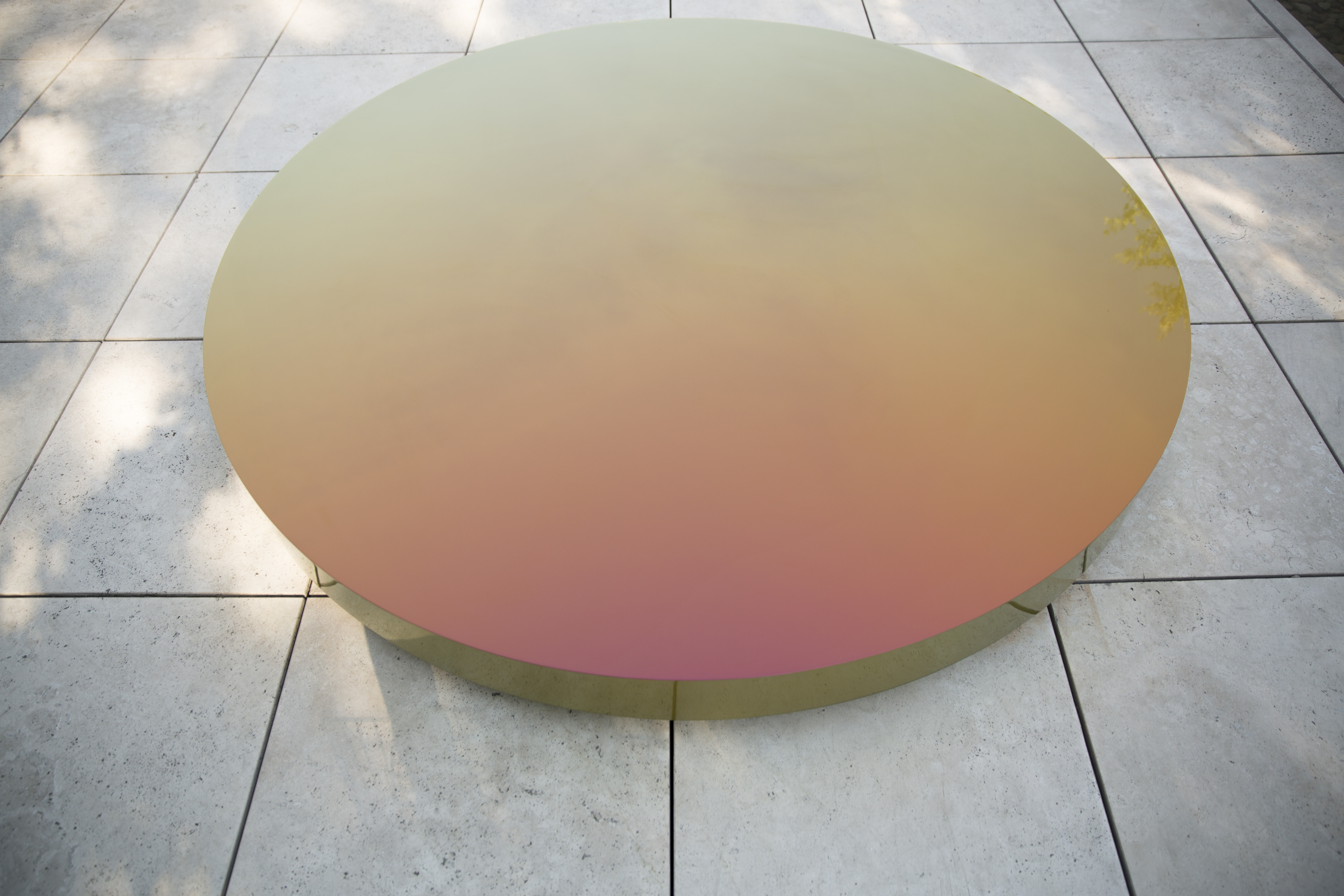

Detail of the scale relation between the piece and the viewer

Photo: Daniel Gil

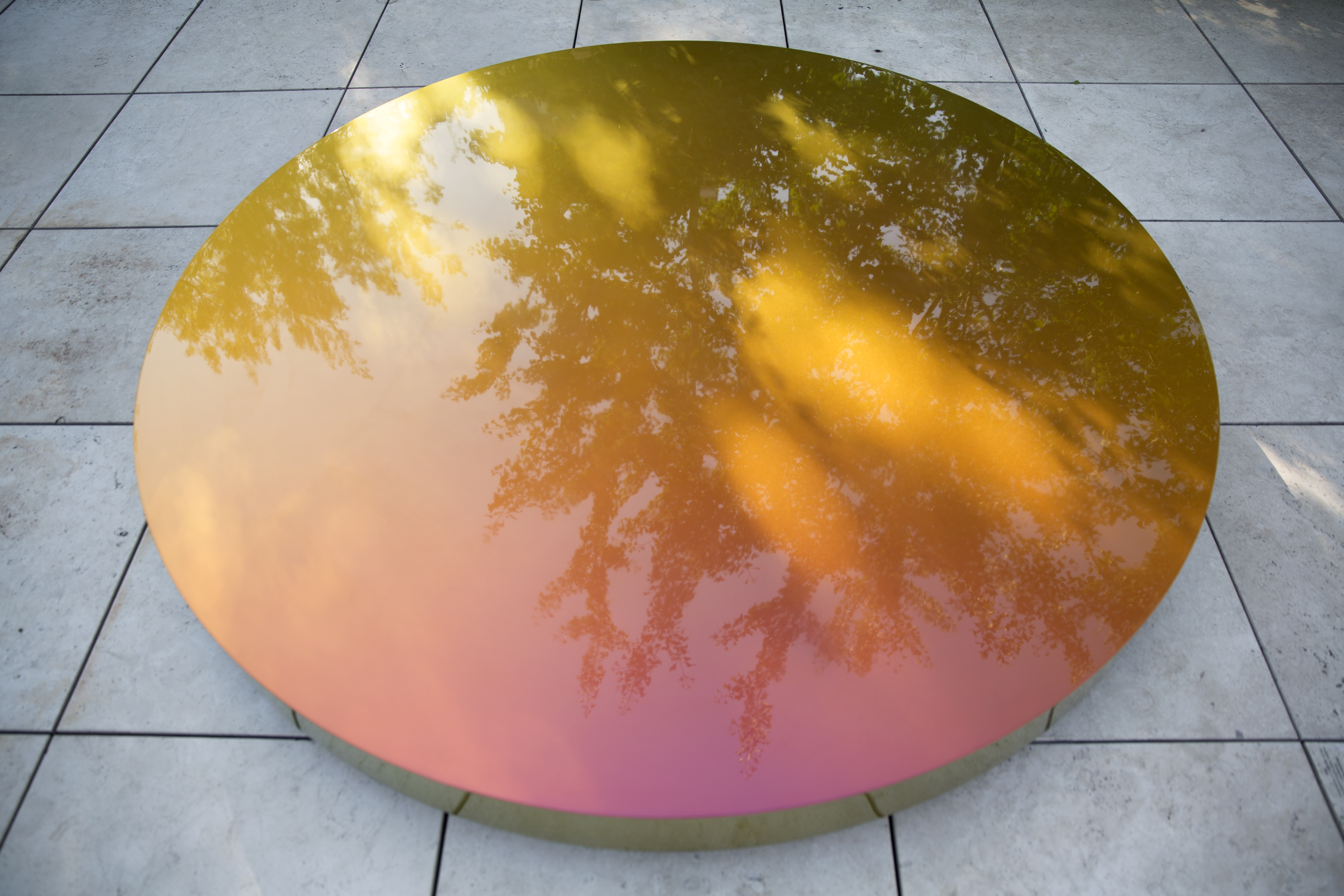

View of the effect created by the lighting and the surface of the industral paint surface of the sculpture

Photo: Felipe Fontecilla

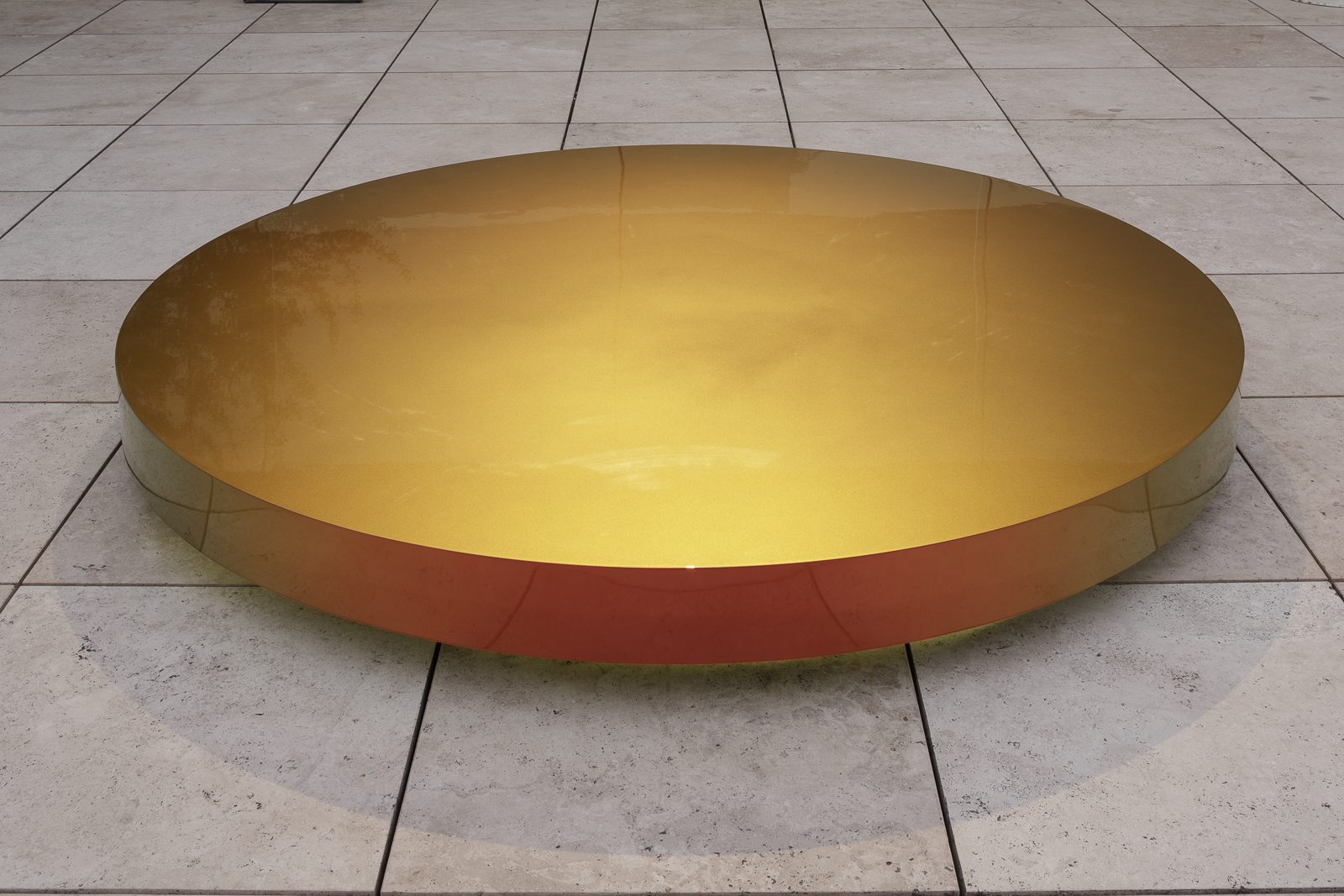

View of the effect created by the lighting and the surface of the industral paint surface of the sculpture

Photo: Daniel Gil

View of the effect created by the lighting and the surface of the industral paint surface of the sculpture

Photo: Daniel Gil

View of the effect created by the lighting and the surface of the industral paint surface of the sculpture

Photo: Felipe Fontecilla

View of the effect created by the lighting and the surface of the industral paint surface of the sculpture

Photo: Daniel Gil

" The loosening creases in your palms show that time has passed in your hands. But you still remember when your hand was the size of a sweet maple leaf, with five points just like your five fingers. They made such a show in the autumn, shimmering like beetle wings in green, gold and red. Sometimes the leaves on the tree would scintillate like fire in the breeze—but when you approached and looked closely, you found that the leaves were flat and opaque.

You assiduously selected a cast of fallen characters, each leaf its own uniquely smeared world of self- contained colour. You took the leaves inside away from the tree, and arranged them with their fingers barely touching on the wall opposite your bed.

Here you could observe them with vigilance. Here the characters would transform against the proscenium of your blank wall.

You lay on your bed and watched. Your eyes slid from leaf to leaf in an effort to perceive time as expressed by colour—or colour being absorbed by time—or a hunger of the sun filling up for its sunsets—you weren’t quite sure."

In fact, you are still unsure.

Yes, it has been explained that the changing colour of leaves in autumn is due to the unmasking of carotenoid and anthocyanin pigments as green chlorophyll dissolves from the cells of the leaf. You know that the more sugar is trapped in the leaf, the crisper the colour. These chemical justifications you have learned by now.

But there is no language for the shift of time between infinite hues.

Yes, it is said there are words belonging to agrarian societies that systematically describe all possible weathers, or the incremental passage of a season, or seasons you didn’t even realize occur. Their indulgent precision is tribute to a persistent desire to articulate cycles. Metaphor is a desire to repeat an experience, cognitively, in the mind of another person, even when the sensory evidence is absent.

To you it doesn’t matter if all these exceptionally precise languages were so idiosyncratic that the words became abstractions. You don’t mind if they have all fallen out of use. Their existence alone keeps you company in your shared desire to articulate a cycle—a sensory pattern, repeatable in time.

You know there are even whole vocabularies to elaborate on contingency, and expectations of the unpredictable. Because there is wisdom in imprecision. Each leaf may be unique, but they follow a pattern.

You resolve to repeat this experiment of observation.

This time you draw what you observe.

First in steps, moving in a circle. You think of it initially as only two dimensional: your steps delineating a shape on a flat plane, the floor. But your body is a form that cannot be flattened—and you are, after all, part of the drawing. So that makes three dimensions. And then you are walking and drawing in time, which makes four.

You have drawn an invisible circle in steps on the floor and already it is a four dimensional drawing.

However, you left no traces.

If you are to do more than just delineate space with your body, but also leave a trace, there is the question of inks and implements, pigments and paints, surfaces and supports. How will you hold this drawing, when it goes from being a four dimensional event to a two dimensional figure?

The question is crushing.

By now we know that colour is not just optical, but also spatial, and that even when we stand still it moves against us. The best option might be to create a horizon, which is both a curve and a line as well as all colours of a space pressing together.

First we must choose a vista, then clear all obstacles in our lines of sight. We may choose to extend the horizon in all directions, or we may be more modest in scale. Observation and drawing require focus.

Now, what remains is to figure out: how to make room for such a luxurious distance of space? "

Text: Caitlin Berrigan

Fragment of: "Horizons"

Year: 2015